Solo exhibition at Centro Cultural Montecarmelo, Santiago, Chile

By

Catalina Mena

Date

AGO, 23 — NOV, 1 2025

I

They say that Buddha's mother dreamed of a white elephant the night before her son's birth. They say that is why this animal is sacred to Buddhism.

Perhaps that elephant that Buddha's mother dreamed of five centuries before Christ is the same one that now persistently returns to Elena Loson's dreams: an elephant that is a symbolic form. But the artist's elephant is not white and immaculate like the one that announced the arrival of Siddhartha. Her animal appears covered in grayish, rough, and rugged skin, marked by lines that trace a mysterious script. A robust body that is always in transformation.

Elena is Argentine. She was born in Rosario, studied in Buenos Aires, and moved to Santiago 18 years ago. Since that decisive crossing of the Andes, Elena has flown over the mountain range countless times. Each time, like the first, it appears to her as a consistent and majestic silhouette dominating the landscape. In some uncertain space in her memory, crossing after crossing, this rocky interval that fractured her biography has been recorded. Let's imagine that for Elena, the mountain range is an elephant.

Trans-Andean. The one who is always on the other side of the Andes; the one who emigrates; the one who is from nowhere; the suspended one; the one who loses and regains her identity; the one who cannot quite say her own name.

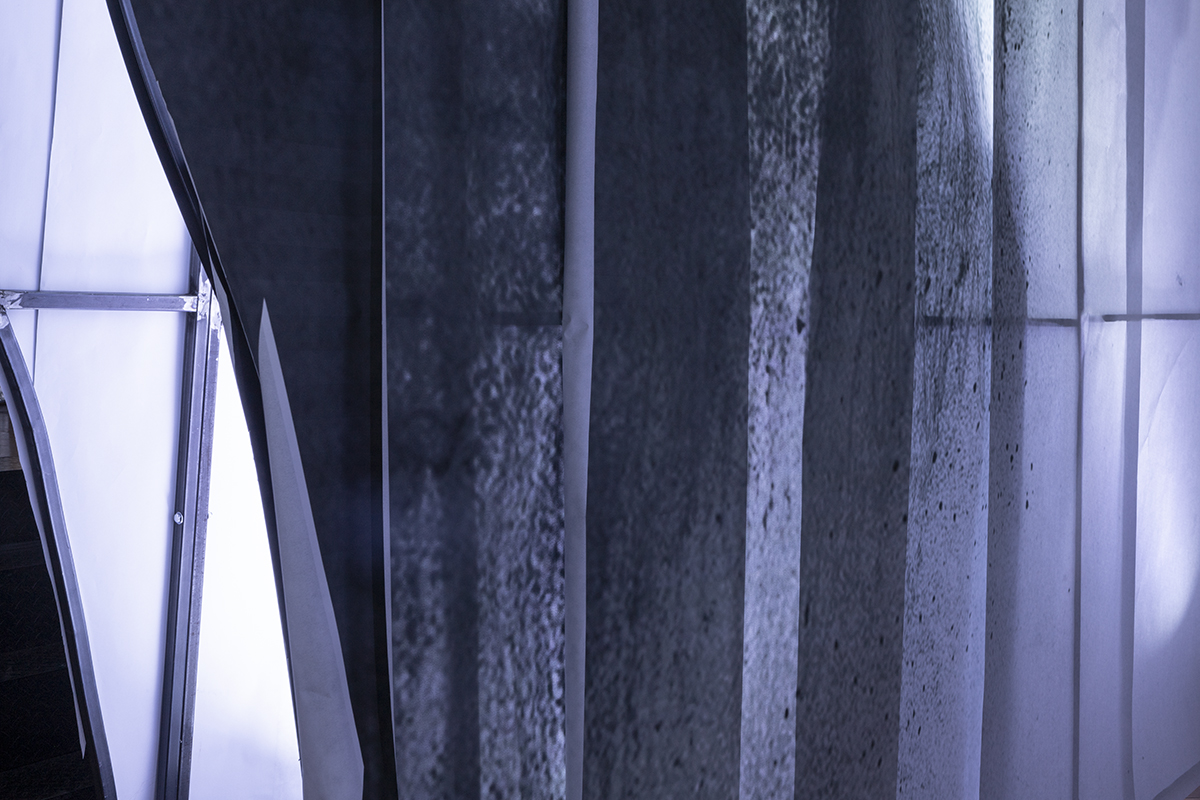

From above, the view reveals rugged mountains that flatten out into expansive plains. It is a backdrop mottled with rocks, earth, and snow; it is an abstract canvas imprinted with materiality. Uncoded skin, a parenthesis of rugged beauty.

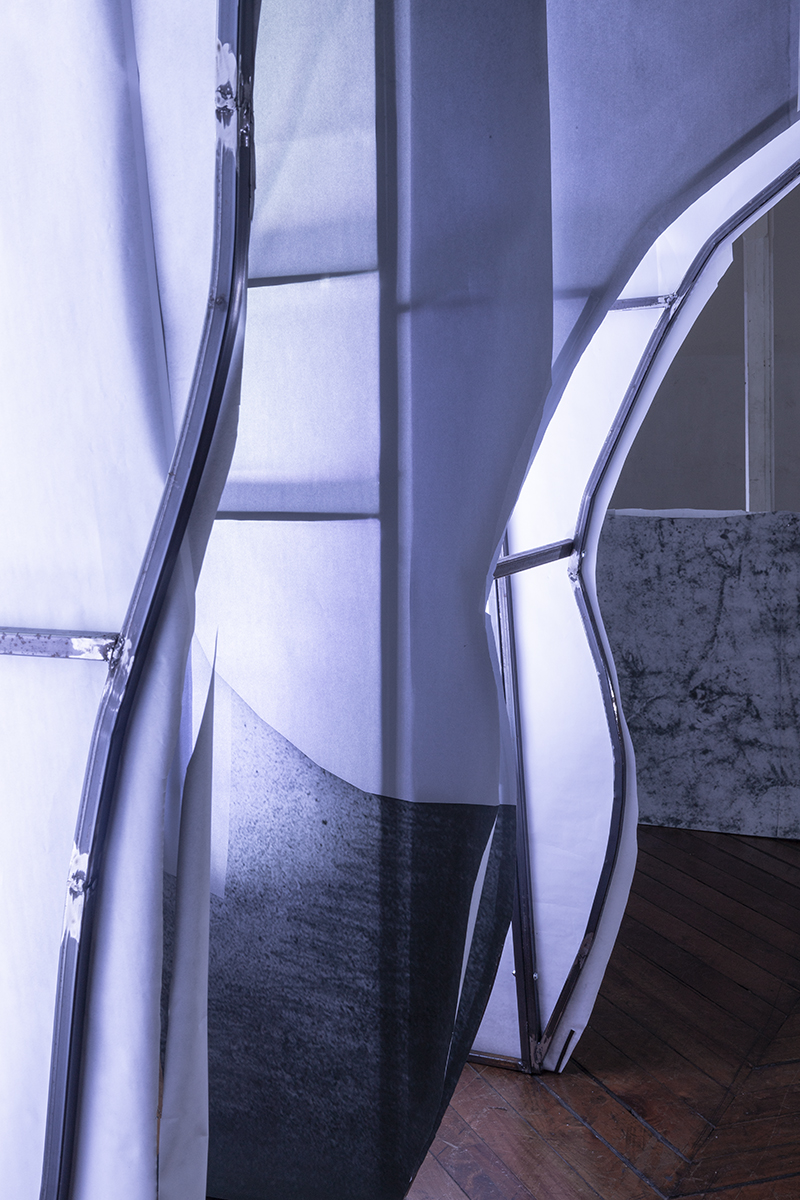

But if Elena were to project herself closer to the mountain range, the image would transform into overlapping volumes that her eyes would be unable to capture. Even so, the silhouettes would be replicated in multiple perspectives: there would be as many mountain ranges as there were positions her gaze could take. And if she threw herself into the mountain range, if her passion decided to enter it, she would set out to find the probable paths and the impossible gorges. Or she could also choose to stay there, still, between the walls, trapped in her silent crevice.

A metaphor for transformation. Spiritual traditions also make the mountain a symbol: a path of ascent to a higher state of consciousness. There, at those heights that border the empty sky, words are erased. Meditators and anchorites retreat to the mountains to meet God: “the one who cannot be named.”

To be trans-Andean is to carry a mountain range inside.

II

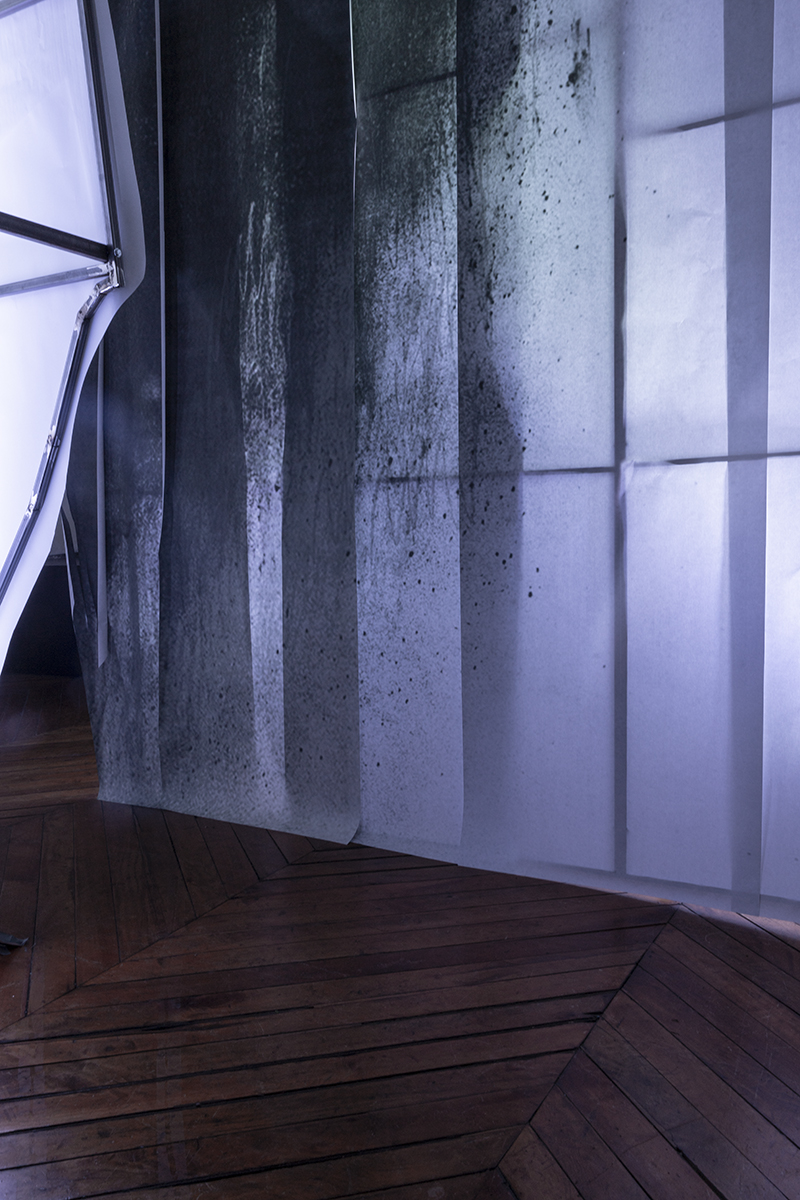

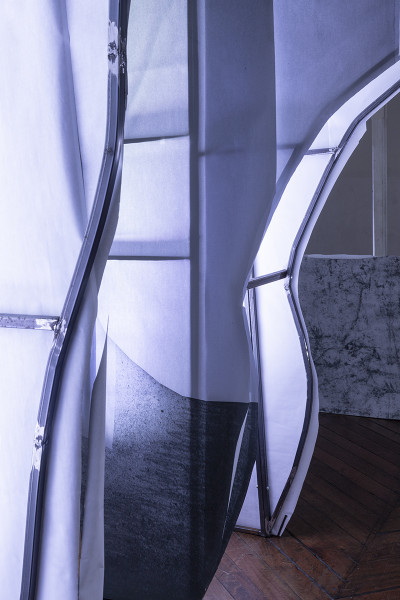

Her work is driven by materialities thrown into his visual configuration process. The images are self-produced, making themselves, like incarnations that disassemble and reassemble. To generate images, she uses graphite, a dark powder that, like volcanic ash, disperses and expands, randomly scattering its blackness. To allow for this overflow, she works on paper on the floor of her studio, as the primary surface for self-generating landscapes.

Paper and black dust. The image renounces color and form: is it an anti-image? Elena embraces her loss and retains her traces, allowing the remnants of the experience to be imprinted on the paper. She saves residues, leaves them dormant, looks at them, reassembles them, transfers them, and thus promotes a visuality that materializes them, cuts them out, and throws them into infinity. It is the permanent search to reconfigure a psychic landscape. Elena pursues, without haste and without respite, that strange place of the elephant-mountain that cannot be named.

If the mountains disappeared, they would continue to exist in memory. Their in-between would continue to resonate as a space to inhabit, experiencing the transition between one image and another.

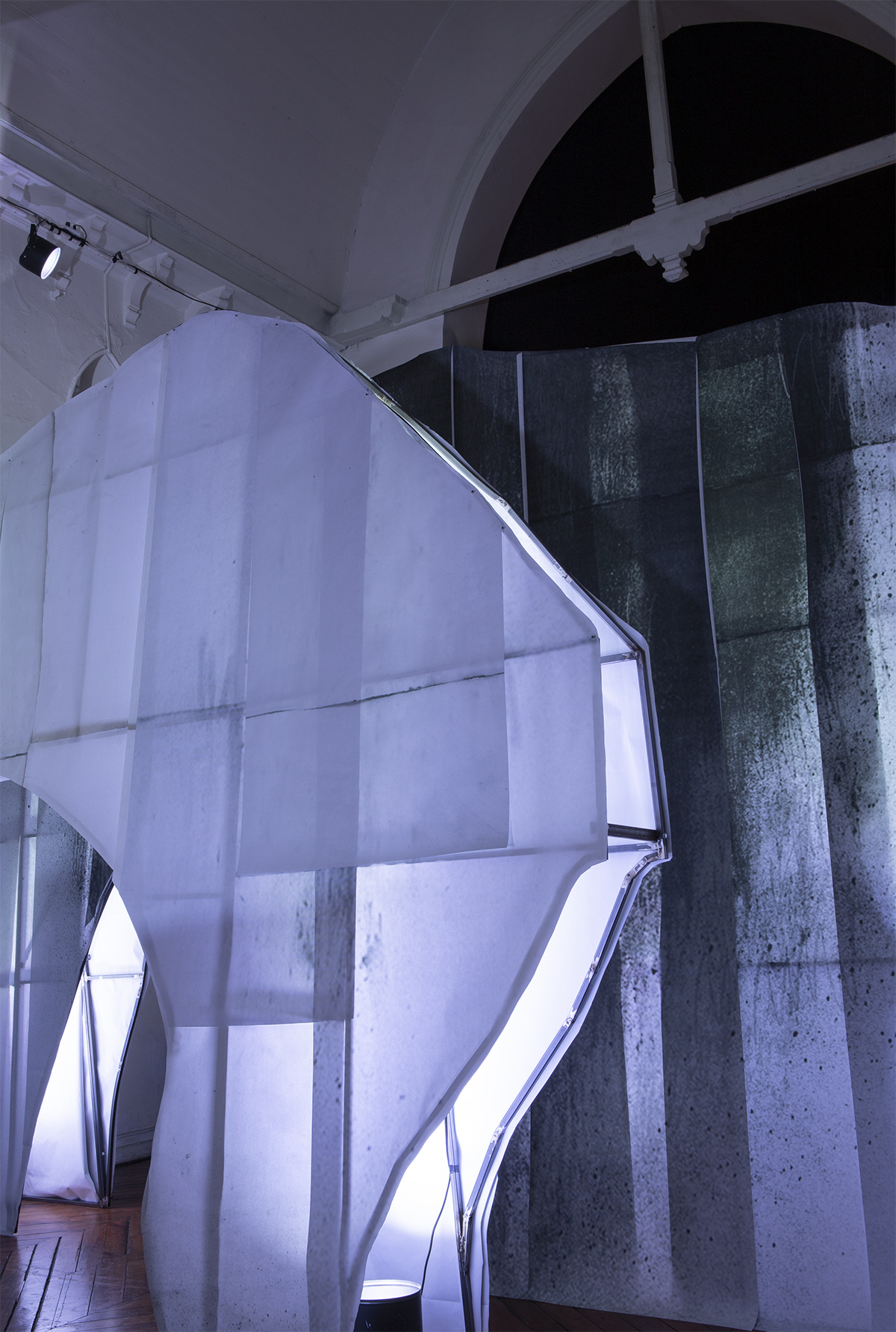

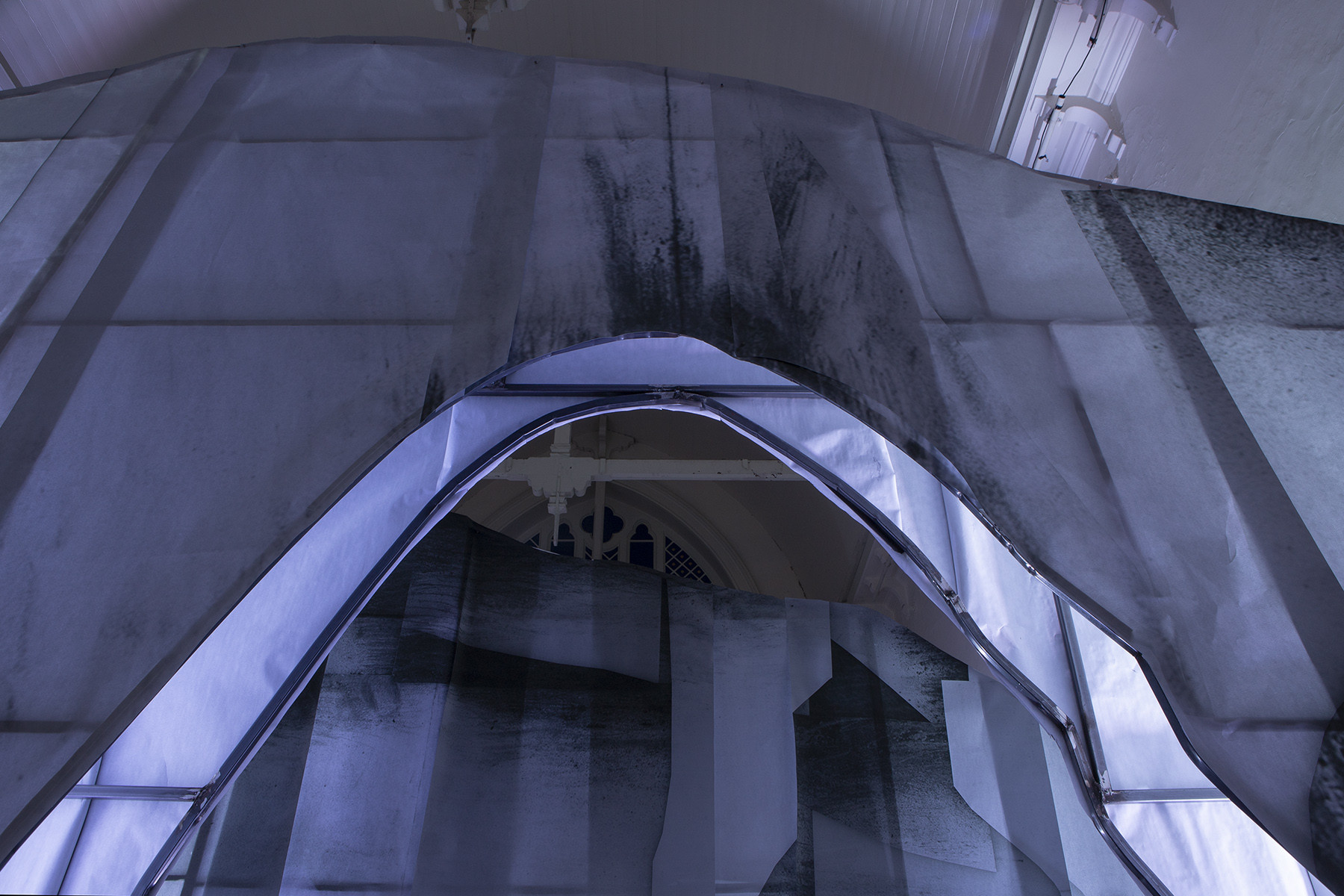

What do an elephant, a mountain range, and a chapel have in common? The answer cannot be found in the code of words. There is nothing to understand. It is those in-between spaces, those nameless spaces, that are traversed by those who throw themselves into the installation that Elena Loson has now set up in what was once a chapel, now an exhibition hall at the Montecarmelo Cultural Center. Here is another fortuitous synchronicity: Mount Carmel is the sacred mountain of the prophet Elijah in the Judeo-Christian tradition.

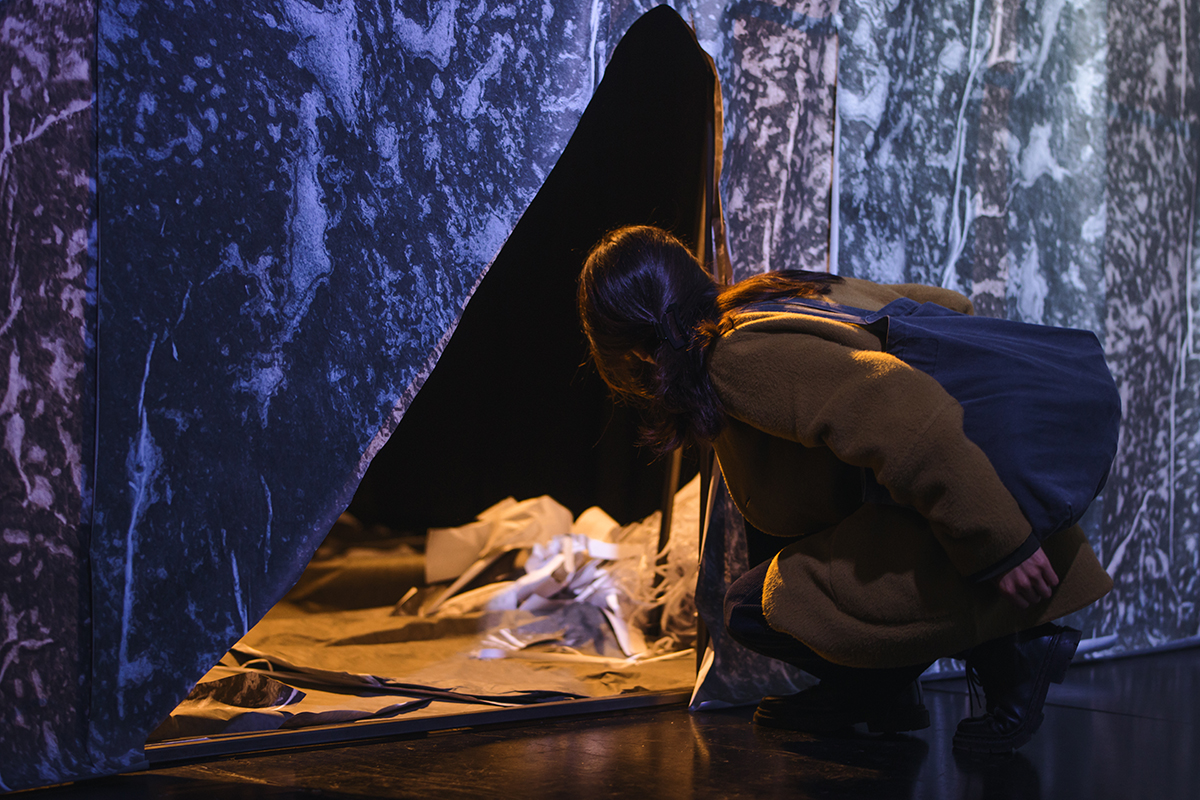

Upon entering this chapel-mountain-elephant, visitors will be able to take in the entire ensemble. Before them will be an imposing mountain range made of overlapping printed textures. To experience it, they will have to discover the transit routes that will place them inside the work, in the middle, as if in an empty interval where things are transformed and come into being. A moment when things lose their identity to acquire another, a moment when, stripped of their own name, we are left with pure presence.

Solo exhibition at Centro Cultural Montecarmelo, Santiago, Chilea Loson

By

Elena Loson

Date

AGO, 23 — NOV, 1 2025

AN ELEPHANT

An elephant's body resembles a sheet of paper that I scribbled on many times and then erased. A piece of paper that I crumpled up and left on the floor of my studio, a gray piece of paper, so neutral, so nothing.

DENSITY

In Santiago, the air is dense. Breathing in Santiago is breathing dust. My studio is a bit like Santiago; you breathe, walk, and live with graphite dust. The floor of my studio is like the skin of an elephant. From time to time, I tidy up, clean, and it seems like fresh air comes in, like when it rains in Santiago and the mountains appear on the horizon. That clear mountain range doesn't last long, just like the clean air in my studio. Both are landscapes.

What would it be like to stand less than a meter away from an elephant?

SCALE AND DISTANCE

I have always liked to use materials on scales different from those for which they were originally made. I have been warned that this project is monumental, but aren't mountains like that? I think about how to fit a mountain into a chapel, a mountain that is also an elephant.

ANCHORING THE DRAWING

And on this scale, which is that of this place and not of another, I would like to learn to draw with scissors, with scraps, with the body, with the air, with layers, and also with the gaze. Drawing like this is like going about any given day. A drawing composed of other drawings that allows for multiple vanishing points and is known to be dismantlable (like a rhizome). It will propose itself as giant and become imperceptible.

THE FINITE

From a workshop I attended, I wrote in my notebook that philosophy is untimely, resistant to the present. Could it be that drawing resists the present just as philosophy does? I'm not sure, but rather that paper is present, aware that death creeps into its material. It is the paper that brings the mountain range to me. It is very similar to the cutouts I make with scissors. The mountain range is nothing more than a cutout in the landscape. I do not see the east in the mountain range; when I move, the horizon shifts.

MOUNTAIN, FOREST OF DRAWINGS, OR IDEA OF AN ELEPHANT

And it is also that mountain range that brings the untimeliness of the present into my daily life, reminding me, every time I cross it, that its immensity makes me fear my smallness, and also my finitude. It is immense, almost infinite.

Will I be able to complete this project? I wonder. And then the elephant reappears, that enormous mass in whose body I see all the lines I would like to draw, to which I return, on which I insist.